第六章:法国大革命伫立于何处

原书及其作者:法国大革命,起于捍卫人权、推翻君主专制,却通向了恐怖统治和军事独裁。这个过程值得警醒。

系列上一篇:What it started | 发端

-----

Chp6 Where it stands

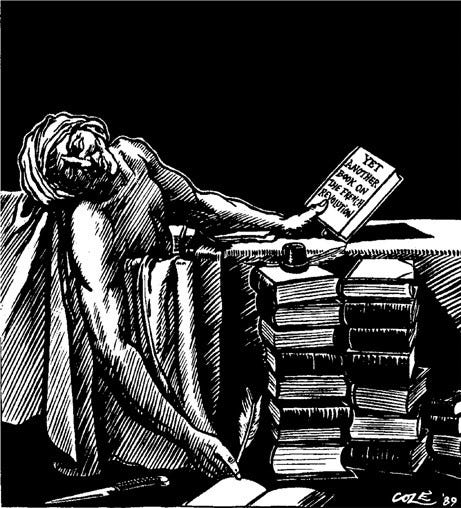

1.A historical challenge —is revolution end?

>p100 ‘The whole business now seems over’, wrote the English observer Arthur Young in Paris on 27 June 1789, ‘and the revolution complete.’ People would repeatedly make the same observation, usually more in hope than conviction, over the next ten years until Napoleon officially proclaimed the end of the Revolution in December 1799. Even then all he meant was the end of a series of spectacular events in France; he was to continue to export them for another sixteen years. Besides, the Revolution was not simply a meaningless sequence of upheavals. These conflicts were about principles and ideas which continued to clash throughout the 19th century, and would be reinvigorated by the triumphs of Marxist Communism in the 20th. Thus it still seemed outrageous to many French intellectuals when, in 1978, the historian François Furet proclaimed, at the start of a celebrated essay, that ‘The French Revolution is finished’ (terminée).

1799年12月,拿破仑宣布法国大革命结束。政治和社会的动荡是该有个终点了,但是大革命中激情浪漫的一面却让人们在另一种意义上仍旧恋恋不舍,毕竟,如果是在更文学或史学的语境中公然宣称法国大革命结束了,这就好像在说即使是那么激情燃烧的梦也该醒了,好像在说,你们一代人投入了那么多心力去关注的事件该结束了,接下来的日子是回到平日。

但是要真正等到人们能做平常心的审视和研究仅作为一历史事件的法国大革命,几乎还要等上一个世纪。

2.The classic interpretation

>p101-102 Its basis was (and is, since despite Furet’s triumphalism it retains many adherents) the conviction that the Revolution was a force for progress. The fruit and vindication of the Enlightenment, it set out to emancipate not just the French, but humanity as a whole, from the grip of superstition, prejudice, routine, and unjustifiable social inequities by resolute and democratic political action. This was the ‘Jacobin’ bedrock, differing little from the professions of countless clubbists in the 1790s. …… From 1898 the great left-wing politician Jean Jaurès began to produce a Socialist History of the French Revolution which emphasized its economic and social dimensions and introduced an element of Marxist analysis. Marx himself had written little directly on the Revolution, but it was easy enough to fit a movement which had begun with an attack on nobles and feudalism into a theory of history that emphasized class struggle and the conflict between capitalism and feudalism. The French Revolution from this viewpoint was the key moment in modern history, when the capitalist bourgeoisie overthrew the old feudal nobility. The fundamental questions about it were therefore economic and social. At the very moment when Jaurès was writing, a fierce young professional historian, Albert Mathiez, was beginning a lifelong campaign to rehabilitate Robespierre, under whose terroristic rule clear ‘anticipations’ of later socialist ideals had appeared. Mathiez set out to stamp his own viewpoint on the entire historiography of the Revolution, and his native vigour was redoubled from 1917 by the example and inspiration of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, which seemed to revive the lost promise of 1794. Robespierre’s Republic of Virtue would live again in Lenin’s Soviet Union.

对法国大革命的经典解读是把它视为一场正义出击,伟大的人民推翻了腐朽没落的封建王朝,将人类从蒙昧之中解放。持这一派观点的政治学家们在二十世纪初的马克思主义兴起和俄国的十月革命(the Bolshevik Revolution)之中仿佛又看到了伟大革命与地上天国的复生。

另外为了避免有人对“经典解读(classic interpretation)”这个词望文生义,这个词在用于描述历史事件的研究学派时,和下面两小节的标题,“修正主义(revisionism)”和“后修正主义(post-revisionism)”是一套的,并不是指这种解读最“正确”,而是一般而言对于一个历史事件最早形成广泛共识的一套观点就被称为经典解读。这时候的时间一般离原本事件还相去不远,研究者有自己的优势,但是很多时候也会掺杂相当比例比如说个人感情或者时局需要之类因素的影响;最初的观点形成流派之后,“修正主义”一般就会慢慢出现,它的主要定义就是严重挑战经典解读,虽然有时会有为了批判而批判的味道,但也往往会随着时间流逝和个人情感冷却而发掘出更多东西;就我个人的感受而言,经典解读的影响逐渐减弱之后,“后修正主义”的出现一般不像修正主义那样有攻击性,虽然后修正主义一般对经典和修正哪边都不爱,但会呈现为一种超脱原有层面的融合再解读,同时也引入更多的史料和更新的研究方法。VSI这个书系在介绍历史评价的时候一般都会把三种流派各点一遍。

3.Revisionism

>p103 Both Cobban and Taylor chose to confront what they called the French ‘orthodoxies’ head-on. It was a myth, Cobban claimed, that the revolutionaries of 1789 were the spokesmen of capitalism; the deputies who destroyed the ancien régime were office-holders and landowners. In any case, Taylor argued, most pre-revolutionary wealth was non-capitalist, and such capitalism as there was had no interest in the destruction of the old order. That destruction, indeed, so far from sweeping away the obstacles holding back a thrusting capitalist bourgeoisie, proved an economic disaster and drove everyone with money to invest in the security of land. Taking their cue from the vast range of questions raised by these critiques, throughout the 1960s and 1970s a new generation of scholars from English-speaking countries invaded the French archives to test the new hypotheses. By the 1980s they had largely demolished the empirical basis and the intellectual coherence of the ‘classic’ interpretation of the Revolution’s origins.

>p104 Tocqueville saw the Revolution as the advent of democracy and equality but not of liberty. Napoleon and his nephew, whom this aristocrat of old stock hated, had shown how dictatorship could be established with democratic support, since the Revolution had swept away all the institutions which, in impeding the relentless growth of state power, had kept the spirit of liberty alive. These insights persuaded Furet that the Revolution had not after all skidded off course into terror. The potential for terror had been inherent right from the start, from the moment when national sovereignty was proclaimed and no recognition given to the legitimacy of conflicting interests within the national community. For all its libertarian rhetoric, the Revolution had no more been disposed to tolerate opposition than the old monarchy, and the origins of modern totalitarianism would be found in the years between 1789 and 1794.

修正主义学者挖出了一位久不受重视的重量级学者的观点,托克维尔(Alexis de Tocqueville),他认为法国大革命自称维护人权而起,据说是要带来民主,带来美德的国度,但它在一边尝试将梦中的民主蓝图带入现实的同时也一边摧毁了和旧社会掺杂不清的许多实质上维护了个人权利与政治自由的文化和制度,没有这些东西从旁保障的民主变成民粹,变成恐怖,最终变成了独裁。

法国大革命确实是以捍卫自由(freedom)和人权为起点的,也意识到了一种新的政治秩序,民主和宪政应该取代旧的绝对君主制(monarchy),但是缺少一点对政治自由(liberty)底线的坚守。几乎就是这一念之差,让法国大革命的终止符从开启稳定的民主新秩序变成了国家权力的扩张。

4.Post-revisionism

>p104-106 The approach of Cobban, Taylor, and those who came after them had largely been empirical, undermining the sweeping social and economic claims of the classic interpretation with new evidence, but seldom seeking to establish new grand overviews. The most they claimed was that the Revolution could be more convincingly explained in terms of politics, contingency, and perhaps even accident. This is largely the approach adopted in earlier chapters of this book. Such suggestions did not satisfy bolder minds. As Furet began to depict a Revolution in the grip of attitudes and convictions which propelled it inevitably towards terror, others, mostly in America, sought wider explanations for revolutionary behaviour in cultural terms. …… Whatever might be said against the classic interpretation, it was at least coherent and comprehensible. By contrast, the ‘linguistic turn’ of post-revisionism, increasingly influenced by philosophers and literary theorists, produced much abstruse material that could barely be understood outside specialist circles.

5.The bicentenary

|

>p108 One of the favourite mantras of the Revolution’s classic interpreters was taken from Georges Clemenceau, the statesman of the Third Republic who gloried in the achievements of the First. The Revolution, he declared, was a bloc. It had to be accepted in its totality, terror and all. It could not be disaggregated. Revisionism, with its emphasis on the contingent, the accidental, and the reality of choices facing those involved, suggested otherwise—as had the young Furet when he and Richet spoke of the Revolution skidding off course. Only by approaching events as contemporaries had to, without an awareness of horrors to come, could regicide, dechristianization, and the guillotine be prevented from throwing their shadows over what preceded them, as they did over everything that followed. Post-revisionists, however, turned against this approach. In emphasizing the cultural constraints that determined what history’s actors could or could not think or do, they opened the way to a determinism not unlike that of the economic and social factors emphasized by the classic historians in their Marxist-inspired heyday. And in insisting that terror was inherent in the Revolution from the start, Furet made it the central issue by which to judge the movement’s entire significance. For post-revisionists of all stamps, in fact, the Revolution was as much a block as it was for those they claimed to have vanquished.

法国大革命至今已经远去超过两百周年了,关于它的热情,关于它的恐怖,关于一切的争论却还远远无法平静。这些不同观点的复杂和他们彼此之间的激烈竞争,简直让我感觉和法国大革命本身一样复杂。但虽然学者吵成一锅粥,但法国大革命与其所启发的人权思想之200周年还是在世界各地得到了广泛的庆祝与纪念。

~ As a subject arousing sectarian passions, the Revolution was clearly far from finished, even for those claiming it was. (p.p. 106) ~

6.The end of a dream?

>p108-109 Since the death of Furet, it is true, new sympathetic analyses of Jacobinism have begun to appear, but most have remained anxious to deny that terror was part of its mainstream. The heaviest blows, however, were not delivered by scholarly revisionists or post-revisionists. They came from the spectacular collapse of Soviet Communism, and the repressive attempts of its Chinese variant, just a few weeks before 14 July 1989, to shore up its authority against students calling for liberty and singing the Marseillaise.

Awareness of the full repressive record of Soviet Communism had been growing at least since Khrushchev had begun to denounce Stalin in 1956. But so long as the Soviet Union continued apparently flourishing and powerful, it could be argued that its Marxist ideology worked and that its bloody past had been a worthwhile price to secure popular democracy. Similar arguments had been used to justify terror in 1793–4, and by later pro-Jacobin historians. When the rule of Gorbachev revealed the whole Soviet edifice to be unviable, and incapable of sustaining its sister-republics in Eastern Europe, this delusion collapsed.

随着共产主义国家通过压迫而行极权主义的本质越来越从那层梦一样的滤镜之下显现,以及苏联于1991年最终解体,最终是破碎的共产幻梦给追随法国大革命经典解释的学者们带来了最沉重的打击。地上天国终究也没有降临,地上天国从不曾降临。

~ If such regimes were the true heirs of the French Revolution, then Tocqueville and Furet were right in their perception that its significance lay not in the enhancement of liberty but in the promotion of state power. (p.p. 109) ~

~ Faith in the benevolent potential of a rationalizing state was the first, and perhaps the last, illusion of the Enlightenment; (p.p. 109) ~

7.Reawakenings

纯属无端联想,这是《攻壳机动队》系列影视作品里的一支经典配乐《傀儡谣》,我也没太搞清楚这些配乐哪首是哪首,反正这首在spotify上的曲名是 Utai IV: Reawakening,标题和这节正好一样。

P112 Persistent if sporadic attempts have been made to disentangle the benevolent intentions of Jacobinism from the terror which accompanied their proclamation in 1793–4: and isolated arguments have even begun to resurface that terror was integral to the survival of the Revolution and all it stood for. It would be surprising, however, if such perspectives ever recover the almost unchallengeable hegemony of the half-century before revisionism. For François Mitterrand’s decision to celebrate the rights of man at the bicentenary was more than a doomed attempt to dissociate the memory of the Revolution from the terror. It was also a recognition that the ideology of human rights was, if anything, more important than it had ever been. Regimes of tyranny and massacre have no monopoly in the heritage of the Revolution. Citizens of modern constitutional democracies whose civil and political rights are guaranteed, and whose life chances are equal before the law, can find much in it to celebrate. The ambition of the French Revolution was so comprehensive that almost anyone living since can find something there to admire as well as to deplore. Nor are all the battles it launched yet over.

~ ‘That, my dear Algy’, says Ernest Worthing, ‘is the whole truth pure and simple.’ ‘The truth’, his friend replies, ‘is rarely pure and never simple.’ (p.p. 114) ~

-----

原书信息:Doyle, William, The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction, 2nd edn, Very Short Introductions (Oxford, 2019; online edn, Oxford Academic, 21 Nov. 2019), https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780198840077.001.0001

评论

发表评论