读书笔记:历史

原书及其作者

牛津通识读本:历史之源(History: A Very Short Introduction),又是一本牛津通识系列,大主题,小开本。这个系列我读到这里是第三本,质量都很不错,作者水平到位,书写结构稳定。如题所述这一本的主题是历史,叙述非常愉快,除了内容上介绍历史学科,本身也像一个叙述历史的实例。

-----

Chapter 1-3

——describe what history has been in the past

|

- 中世纪及以前,最初诞生的历史是过去的故事,和故事的叙述。叙述中带着修辞,叙述者的目的,和叙述者自己的解释。早期史料中,“史实”的概念和文学风格混杂不清,对历史的观念则是认为应以记述政治为全部目的。

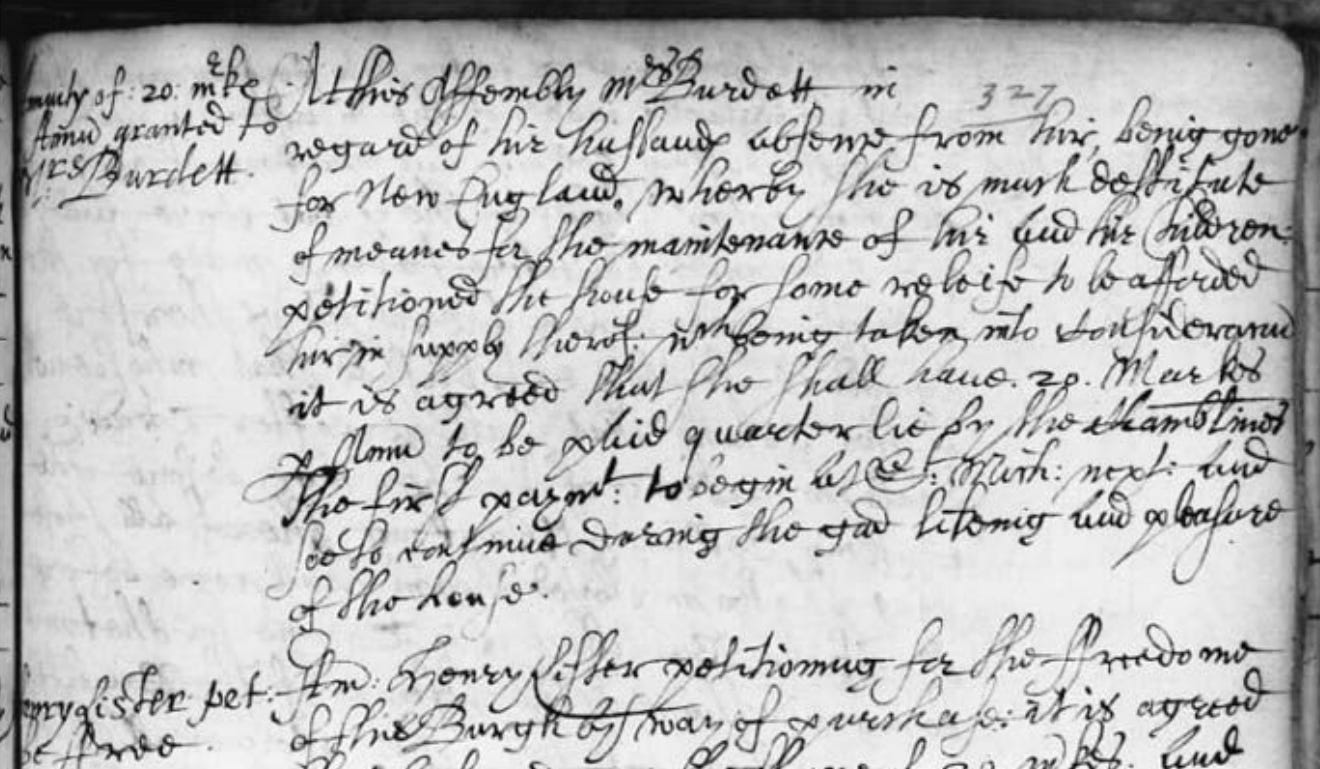

- 大概在宗教改革到工业革命的年代,欧洲16、17、18世纪左右,又或者说从中世纪向现代进发的大节点上,历史开始发展为专门的学科。“事实”的概念开始形成,历史从文学的温床里脱出,逐渐成为旨在记述“真实”故事的学科;史料研究逐渐开始细致,除了史料本身内容,史料语言中自带的时代差异也开始被注意到,一片混沌中,“过去”与“现在”概念上的微妙差异开始进入研究范围;历史的“动机”(causation of history),即历史发展由什么推动的问题开始进入史学家的视野。

Chapter 4-5

——show how one might set about ‘doing‘ history

>p62 These are important stages, and something similar is present in every history written: A clue that pushes the historian towards a particular set of sources. Historians make choice and decisions before they ever lay eyes on the evidence. So perhaps it would be more truthful to say that one way in which history begins is with sources. Another way in which it begins is with historians themselves: their interests, ideas, circumstances, and experiences.

历史的研究,首先是大量的文献工作,检索和分析、理解大量的档案文件。档案是前人写下的文件,所有档案都带有不同的原始立场、写作目的,和这些特性中所能被解读出的潜在信息。史学家的工作(how to “doing“ history)就是从这些浩如烟海的证据出发,用自己的解读和猜测将故事的“真实”补全。也是因此,历史不只是死去的故事,而是对过去故事的鲜活解读,历史和其他所有学科一样都是永在现在时中活着的学科。

有一个深入做历史的油管号 歷史衛視 History Channel 他发的这条推文提到历史地图的难以捉摸,增加了我对于做历史这个概念的感性认知。

|

>p78 And always there are new questions to ask. Why? Because of new ways of looking, because of other things seen before or after, because of different paths travelled. But primarily because there are gaps, spaces, elisions, silences. The sources do not speak, and they do not tell all. This is, as a French historian recently put it, at once the impossibility and the possibility of history: that history, which aims at the whole truth, cannot ever reach it (can only ever be a true story) because of the myriad things which must remain unknown; but that it is this very problem which allows - or rather, demands - that the past be a subject for study, instead of a self-evident truth.

- 随着时间线推进,对历史的解读开始越来越发达,历史研究的内部开始分化出政治历史、经济历史、社会文化史等等分支。长线的宏观历史叙事(Grand Narrative)和纷繁复杂的研究方法(approaches)开始出现,比如横跨16、17、18、19世纪的现代化进程叙述。宏观叙事拾取其所重视的史料而忽略另一些部分,为其中的组成事件的意义提供坐标。

>p92 In trying to decide what 'causes' something to happen, historians can draw on a number of different theories, and fall back into a variety of positions. Most would admit that, except at the most simple level, everything has a plurality of causes. And what then happens on account of those causes becomes, in turn, the cause of something further still. Historians try to make patterns from these intricate series of events; sometimes very simple patterns, such as a narrative of 'important' men, and sometimes very complex patterns, of ideologies, economics, and cultures.

- 对历史动因的思考从伟人史观逐渐出离,认识到社会经济因素和人们观念之间循环往复的相互影响塑造着行为。

>p91 'Effects' are no less complex than origins. Some of the effects of the colonization of America would be the deaths of hundreds of thousands of native Americans, the development and continuation of slavery, the beginnings of England's economic decline over a very long period of time, the establishment of new ideas about government and politics, the cold war, the space race, the multinational society in which we now live. Who could say that the Pilgrim Fathers imagined such outcomes? And who would dare to draw a line under those effects, and say 'this is where the story ends'? For nothing ever ends, really; stories lead to other stories, journeys across a thousand miles of ocean lead to journeys across a continent, and the meanings and interpretations of these stories are legion. 'Origins' are simply where we choose to pick up the story, dictating (and dictated by) what kind of story it is we wish to tell. 'Outcomes' are where we wearily draw to a close.

- 另在对历史动因的追问之外,历史的“结果、影响”也逐渐成为了鲜活丰满的概念,人们开始认识到,一个起点的起因初心和它的发展与结果是独立的东西。

|

Chapter 6-7

——present some thoughts on the status and meaning of history and truth

|

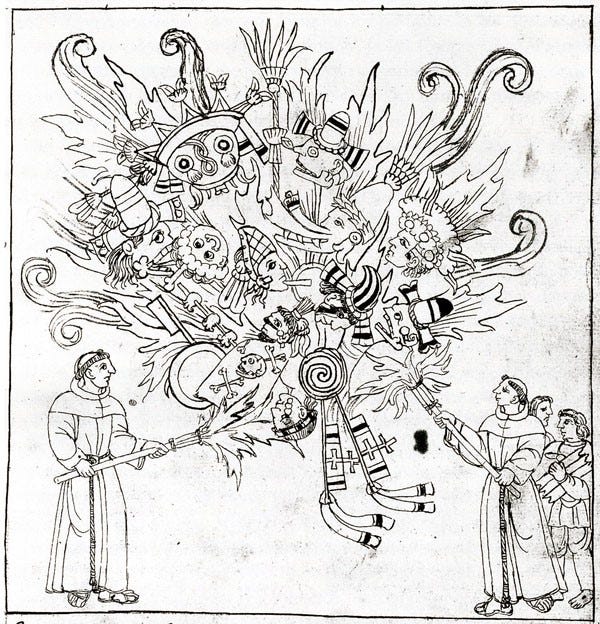

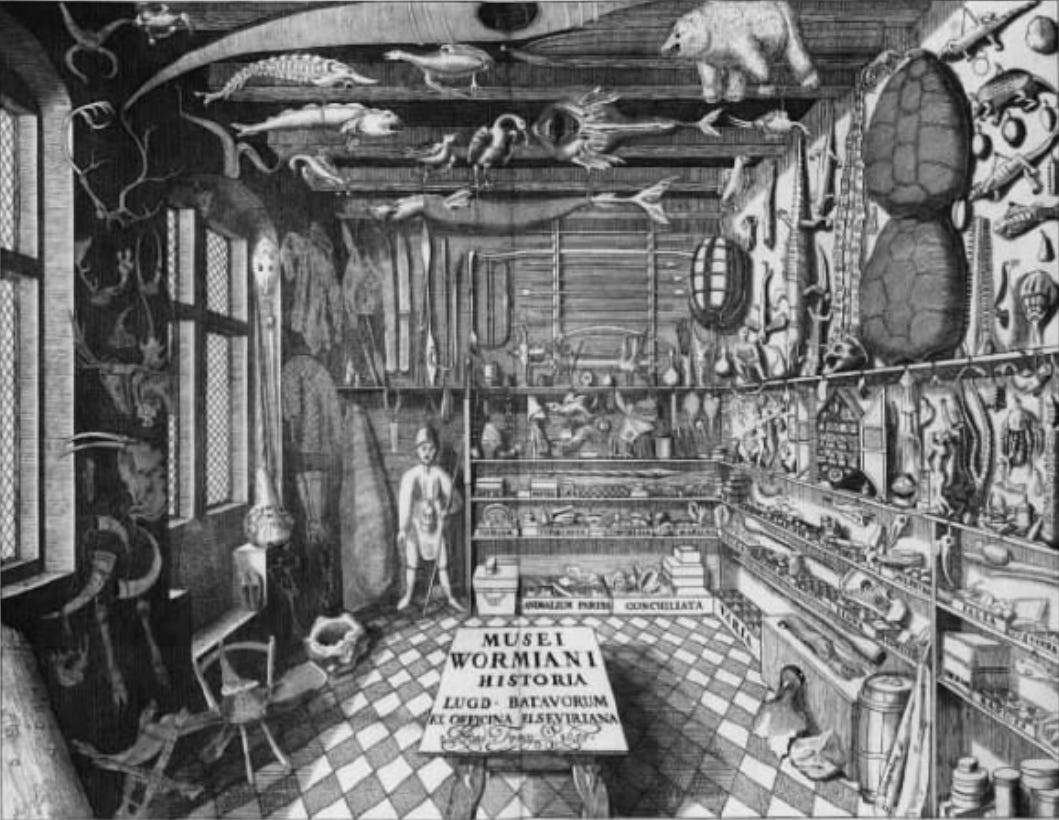

| P39, Ole Worm’s antiquarian cabinet of curiosities (1655) |

>p96 There is, however, one core difference that divides all historians into two groups: those who believe that people in the past were essentially the same as us; and those who believe that they were essentially different. You might remember this division from our earlier chapters: David Hume thought that all 'men' were so much the same in every age; L. P. Hartley suggested that the past is a foreign country where they do things differently from us.

对“过去”与“现在”的不同之处的认识日益发达,史学家开始为历史划分经纬,以作为坐标描述人类在历史中的流变,然后自己也在自己时代的流变之中试图将一些流变了的故事书写给一些流变着的听众。

>p100 Anthropologists, who have spent their time studying and analysing other cultures, have provided useful frameworks for thinking these things through, giving historians a language for discussing ritual, the arrangement of social space, the conduct of one gender to another, and so on. Mentalité has become a shorthand term for summing up all of the various assumptions, practices, and rituals found in past eras. …… We should note first of all that the idea of mentalité also involves two other cognitive operations: dividing the span of human history into periods; and reading historical evidence in ways never intended by its creators.

这种将历史从后见之明上划分时期、赋予特点(symbolic patterns to people’s actions, ways of thinking, spirit of an age, mentalité, etc.)的操作和前面提到的宏观叙事、研究方法这些大概念一样,拾取一些声音、减弱一些声音,有时也曲解一些声音,只有对这些操作本身有所意识,才能良好的运用。

这时的人们也开始询问历史研究的意义(what we think history is for)。

>p115-118 This is to suggest two things: first, that the polarity of fact and meaning is untenable, as no ‘fact‘, no ‘truth‘, can be spoken outside a context of meaning, interpretation and judgement. Secondly, that truth is therefore a process of consensus, as what operates as ‘the truth‘ (what gets accepted as ‘the true story‘) relies on a general, if not absolute, acceptance by one’s fellow human beings. … To return to the question of Truth, by way of these thoughts, the danger in deciding in favour of one account against another is that it aims to mould ‘history‘ into a single true story. This is the logic too of seeking an ‘objective‘ or ‘scientific‘ history - neither of which is possible, in the way that they’re meant to be. Both are attempts by subjective historians to present their version of events as the only possible version.

在追寻“真实”的路上,研究历史的人有时会将“真相”(a truth that is grounded in meaning and perception)和“事实”(inert fact and prosaic ‘reality‘)的概念对立起来,但其实这两者的体察和叙述都应该由同样素养的零件组成,好的历史研究既需要有自己的洞见,也要有对史料细节的观察。试图决定一个排他的“正史”、“真相”,只会导致一种特定偏好压倒其他所有探索,因为任何一种历史都带有自己本身的偏好。

>p118-119 None of this, however, means that historians should abandon the ‘truth‘ and concentrate simply on telling ‘stories‘. Historians must stick with what the sources make possible, and accept what they do not. They cannot invent new accounts, or suppress evidence that does not fit with their narratives. But, as we have seen, even abiding by these rules does not solve every puzzle left by the past, and cannot produce a single, uncomplicated version of events. If we can accept that ‘truth‘ does not require a capital ‘T‘, does not happen outside human lives and actions, we can try to present truth - or rather truths - in their contingent complexity.

历史无法被彻底探索完毕,也无法教我们预知未来,但它给我们提供无数的思考原料,让我们加以理解自身,看到自身的发展;历史给人以身份认同,但这种身份有时也固化矛盾,阻碍人的思考和选择;历史也时时提醒我们,我们以为理所当然的东西可能并不是很理所当然,人文社会中的现象总有一个源于人的起点,对更广阔现实的探索应该永远鲜活。

-----

原书信息:Arnold, J. H. (2000). History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285352-3

评论

发表评论